On Monday, May 11, 1970, Portland State students had been on strike for nearly a week. The campus had been closed since the previous Thursday, and the mayor, the commissioner of parks, Gov. Tom McCall and the citizenry were running out of patience.

At the time, the South Park Blocks weren’t the pleasant pedestrian promenade that they are today. The streets were major thoroughfares and ran all the way through. The students were not only occupying the park, they had constructed barricades of lumber, park benches and miscellaneous debris to preventing traffic from flowing through the area. Tensions flared and violence was imminent.

The incident referred to as the Park Blocks Riot” was captured on film by PSU students and made into a documentary with help from the University’s Center for the Moving Image. There is a VHS version of The Seventh Day available in the library.

But this Friday—the 42nd anniversary of violent confrontation between campus protesters and police—5th Avenue Cinema will screen a virgin 16mm copy of the film.

The screening will be followed by a discussion with some of the people present the day of the riot. The event is the brainchild of PSU graduate student and public history major Doug Kenck-Crispin, the resident historian at orhistory.com, which created the podcast series Kick Ass Oregon History.

Kenck-Crispin came across the film during his research for an undergraduate project that he did on the Park Blocks Riot.

“It seemed just obvious that the day that Portland police beat up a bunch of poor hippies in the park blocks would be a fantastic episode in our series,” he said. “Showing the film at a live event just seemed to be a natural tie-in.”

The Occupy protests have given this historical document a fresh relevance, a fact which isn’t lost on Kenck-Crispin. The podcast calls the Park Blocks Riot “the first Occupy Portland.”

Kenck-Cripsin will speak at the event, as will PSU history professor David Horowitz, who had been an assistant professor at the university for two years in 1970. Horowitz was one of 134 professors who supported the student strike, and he took part in the May 11 protest.

“There were several so-called radical professors, and I was part of the group,” he said.

He explained that the police action was spurred by an act of civil disobedience in which the students sat in front of a medical clinic tent that served the protest. The Portland Commissioner of Parks, Frank Ivancie, told the students that their permit had expired; the students disagreed. The rest is history.

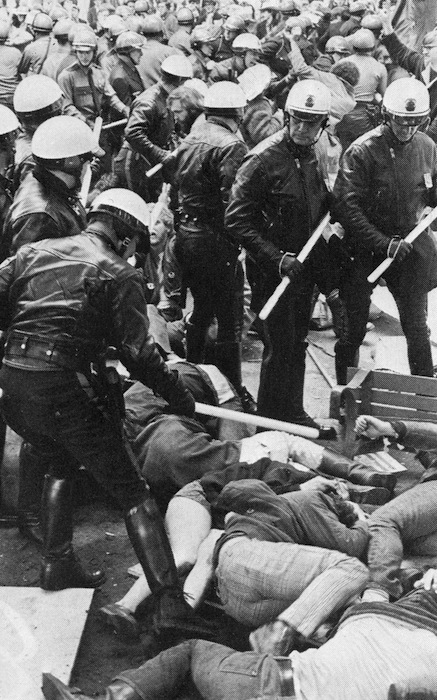

Horowitz told Kick Ass Oregon History, “It felt really ominous. Looking at these guys in their white helmets and their three-foot white batons, we weren’t sure what was going to happen.”

The police moved in, swinging at the students. Horowitz, to his chagrin, spent most of the time moving an injured student into the Smith Memorial Student Union for medical attention. He disagrees with the characterization of the event as a “riot” and said that the decision to put down the protest with force was a political one.

“It was a police action. It was a political decision on the part of the mayor. He didn’t care if the permit was still good,” he said.

Portland, he explained, was a much more conservative place then, and the citizens were fed up with student protest. They wanted the restoration of order.

The Seventh Day reflects that sentiment. Negative commentary from Portland residents pepper the footage of cops in riot gear, advancing on sitting students—students retreating with head wounds.

In one particularly resonant segment, students march up Southwest Broadway carrying signs as onlookers stare from shop windows. Broadway looks a little different, but the protesters look like those of today. In fact, part of what’s so striking about the film is how little has changed. The impression is that the roles never change; new people are just born to fill them.

Yet Kenck-Crispin points out an important difference: “The mayor [Terry Schrunk] came in with some cops and they started swinging batons. You look at Lownsdale [Square] when they wanted to evacuate that, and Sam Adams said, ‘Whoa! Hold on, let’s approach this thing a little bit differently.’ But it came to a point there where it was pretty close to the baton swinging.”

These comparisons will likely be part of the discussion following the screening. Horowitz speaks fluidly and at length about the protest movement of that era and its lessons for the protests of today. His ideology has changed somewhat from those days and his understanding of protest tactics have matured.

“There are some similarities [between Occupy and Vietnam-era protests] and probably some similarities in terms of vulnerability. I actually think it was a mistake to do the protest in front of the damn hospital tent. That wasn’t about the war, like when Occupy gets fixated on sleeping in the park, just for the sake of taking over the park,” he said.

For his part, Kenck-Crispin is enthusiastic about showing PSU history to current PSU students.

“I could have hosted this thing at the Bagdad [Theater], I could have hosted it at the Hollywood [Theatre], but this event really should happen at PSU at 5th Avenue Cinema,” he said.

There will be beer and wine for purchase. In keeping with the theme of all things groovy, musician Josh Feinberg will play his sitar.

Read this article in The Vanguard HERE. And don’t forget to COME SEE THE FILM.